It can be tempting to think that writing a children’s picture book is easier than writing a full-length novel. however, a picture book actually requires the same important storytelling elements as a novel, such as well-drawn characters and an intriguing plot, just in a much smaller space.

The good news is that if you can accomplish these things (with compelling illustrations for starters!), you’ll be poised to inspire the imaginations of young readers, who are always looking to welcome their next beloved picture book into their library. .

You are reading: Writing children’s picture books

To help all you aspiring authors who want to be the next Maurice Sendak or Margaret Wise Brown, we’ve put together this 8-step guide on how to write a children’s picture book, plus tips for editing, illustrating, and publishing. that!

let’s start with the basics…

1. propose your idea

Successful picture books are the ones that strike the right balance between appealing to two different audiences: while a picture book is intended for children, it’s ultimately the parents who decide whether or not to buy it — or to read it aloud. (That being said, appealing to and entertaining adults shouldn’t take priority over the children you’re writing your children’s picture book for.)

Fortunately, having an idea for your picture book is essentially the same as having an idea for any book, for any age category. it’s how you present that idea that will differ. For example, your picture book idea could focus on specific childhood experiences, such as:

- losing a favorite toy

- bedtime struggles

- imaginary friends

- fear of the dark

but when you break those ideas down to their essence, you’ll find that their concepts are universal:

- attachment

- overcoming challenges

- friendship

- fear

In that sense, successful books fail to connect with readers because they present an idea that has never been explored before. they are successful because they convey themes in new and interesting ways. Sure, Goodnight Moon has been helping parents put their kids to bed for over 70 years. but you can be sure that bedtime stories will keep hitting the shelves for a long time, as long as they look at the subject from different angles.

To make sure your idea is strong, ask yourself the following questions:

- Am I presenting the theme of my book in a way that is relevant to children?

- Am I exploring the themes of my book in a way that feels unique?

- Will my book appeal to parents? this question may be more difficult to answer, but if you can say “yes” to the first two questions, you’re probably on the right track here as well. Also, as an adult, think about the picture books that have stuck with you, and then make a note of the elements that keep the book fresh in your mind as an adult.

If you’re having trouble nailing down the central concept of your book, this guide to story themes might help. Or maybe you’re looking for inspiration, in which case this list of the 100 Best Children’s Books of All Time is sure to get your creative wheels spinning.

2. identify your reading category

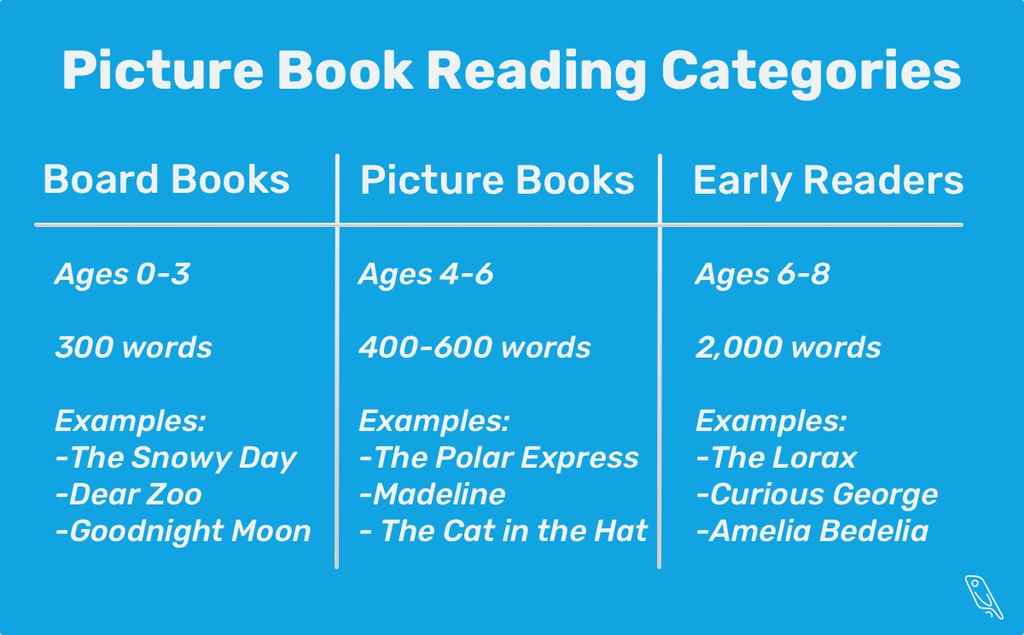

Let’s take a quick look at the different types of picture-based books, as well as some popular examples of each.

board books

- reading age: 0-3 years

- length: about 300 words

- examples: bill martin jr.’s chicka chicka boom boom, the very hungry caterpillar by eric carle, the snowy day by ezra jack keats

Illustrated books

- reading age: 4-6 years old

- length: 400-600 words

- examples: where the wild things are by maurice sendak, the polar express by chris van allsburg, madeline by ludwig bemelmans

early readers

- reading age: 6-8 years old

- length: around 2000 words

- examples: amelia bedelia by peggy parish, the lorax by dr. Seuss, Curious George by H.A. and margaret king

Chapter books, for readers ages 9-11, also often contain illustrations. however, they are often black-and-white sketches rather than full-color illustrations, and images are used to supplement the story rather than help tell it. If you’re looking for more in-depth details on the reading ages of various children’s books, check out this guide to writing a children’s book or sign up for the course below.

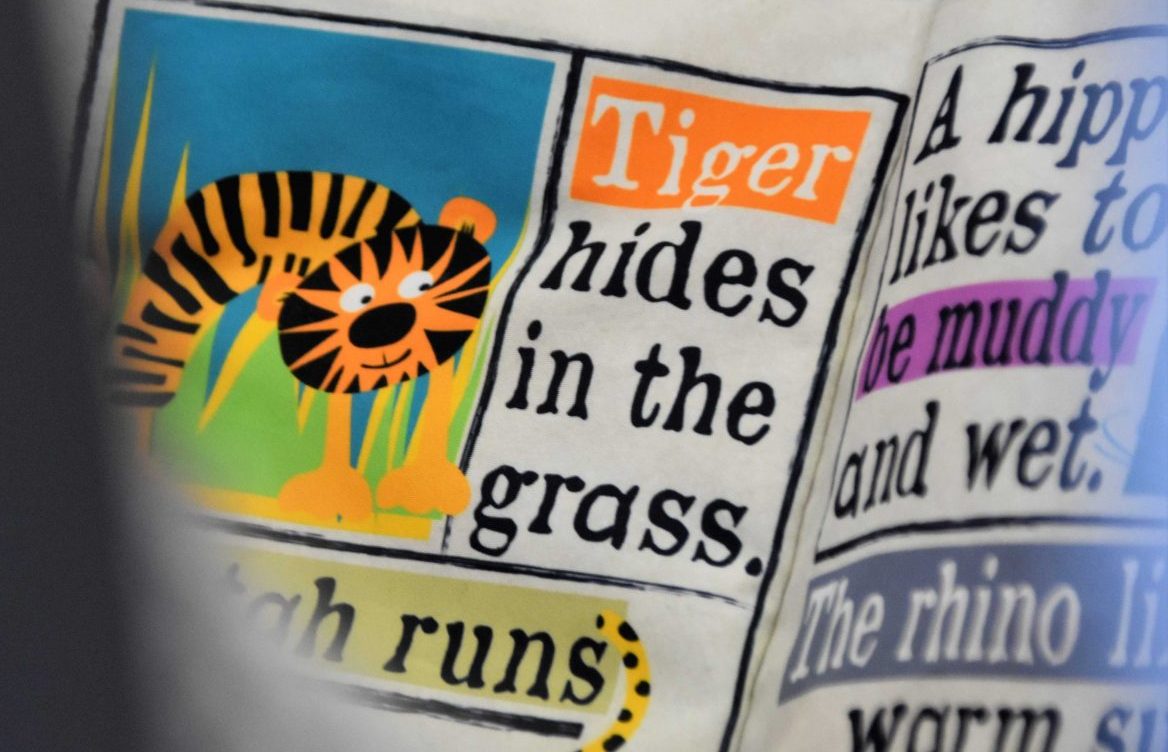

3. work on your narrative voice

Even though many kids are able to read to themselves by the time they’ve graduated to the picture book and early reader categories, all books that rely heavily on illustrations are often still read aloud. That’s why rhyming in children’s books is pretty common — it creates a fun and engaging vocal storytelling experience. (Still, rhyming is not always a good idea for picture book writers — more on that below!)

In addition to prose that sounds good out loud, there are other factors to consider when it comes to the narrative style of your picture book:

vocabulary

If you’ve ever casually mentioned a word in conversation with a child, only to have them ask you what it means and bewilder you as you try to figure out a way to explain it, you’ll know the importance of adapting their picture book vocabulary to the range age of your readers.

This, again, means striking the right balance. you want the vocabulary you use to be accessible to children. at the same time, he also wants to offer young readers the opportunity to broaden their understanding of the language, with the help of illustrations. As kids editor Jenny Bowman says, “Kids are smarter than you think, and context can be a beautiful teacher.”

If you’re not sure if your book’s vocabulary is spot on, your best bet is to read other picture books to compare and get feedback from parents and children themselves. (but we’ll talk about that later).

repetition

on the note of helping youngsters expand their vocabulary and reading skills: repetition plays a key role in many picture books!

The use of repetition allows children to anticipate what the next word or sentence in a story might be, encouraging them to engage in the act of reading and follow along.

examples include husky bear by karma wilson, grizzly bear, grizzly bear what do you see? by bill martin, and a day in the eucalyptus, eucalyptus tree by daniel bernstrom. oh, and just about anything from dr. seuss, of course!

rhyme

See Also: William Faulkner – Book Series In Order

As with repetition, rhyme can help children anticipate the next elements of a story. It can also make for a more fun and memorable reading experience: how many of us can still recite “I don’t like green eggs and ham, I don’t, sam, I do!”

however, as all aspiring picture book authors know, it’s incredibly difficult to get rhymes really right. A wonderful book can be brought down by a sloppy rhyme, and unless you’re Dr. Seuss’s equally talented grandson, publishers are likely to be wary of his rhyming manuscript. so going the rhyme route is taking a risk.

but if you decide that rhyme is your style and anything else just doesn’t work (see what we did there?), remember that the story should always come first. don’t sacrifice plot or any other important story elements for the sake of your rhymes.

point of view

point of view refers to the perspective of the narrator. if a story is told from…

- first person, the narrator is the person you are telling the story to and will use words like “me” or “me.” for example, i love you forever by robert munsch.

- second person, the narrator places the reader within the story and uses words like “you” or “you”. for example, in new york by marc brown.

- third person, the narrator tells the story from outside the action. in third person limited, the narrator can only reveal the thoughts and feelings of a particular character, while in third person omniscient, the narrator knows the thoughts and feelings of all the characters. this view uses words like “he” or “she.” for example, corduroy by don freeman.

Deciding which point of view you want to use is a big decision when it comes to how to write a children’s picture book, and they all have their strengths, depending on the story you’re telling. i love you forever, for example, it’s a book about unconditional love and it’s a comforting read (of course, until you’re older and it suddenly becomes real heartbreaking!), so it makes sense that the narrator would speak directly to the reader, using second person language such as “you”.

learn more about each narrative perspective in this point of view guide.

4. develop attractive characters

Writing a picture book is not an opportunity to cut back on the work that goes into creating realistic, well-rounded characters with their own motivations, struggles, strengths, and weaknesses. yes, you’re telling a story with far fewer words than a novel, and you have the benefit of using illustrations to help convey meaning, but your characters still need to feel like real people.

Think about the books you enjoyed as a child. they likely stood out to you because you loved or related to their characters. If a parent or guardian knows that his or her child has become a fan of a specific character, he or she is also much more likely to continue buying more picture books about that same character. therefore, taking the time to write fully realized characters will not only allow you to hone your craft, but also allow you to build a fan base.

Note that the characters do not need to imitate children to attract them. You don’t need to worry about alienating your customer base by writing characters that don’t look, sound, or act like they do. in fact, striving to create the most attractive cast possible is a ticket to creating forgettable characters. Don’t be afraid to come up with unique characters that will connect with children in a special way: think of how many children have animals, aliens, or anthropomorphized objects near and dear to their hearts.

To help you on that front, we have three helpful resources:

- a character profile template to help you build your character from scratch.

- a guide to character development to help you really focus on what makes your characters tick.

- a list of character development exercises you can turn to whenever you feel a sense of disconnection with your characters.

Don’t forget to consider the importance of giving children access to characters that represent them. Read here about the importance of diversity in children’s books.

5. show, don’t tell

A piece of advice extended to all authors, “show, don’t tell” actually puts picture book writers at an advantage because of the illustrations that accompany their books! And you should absolutely rely on your illustrations to convey things to readers, allowing you to save your limited word count for other things.

Of course, the concept of “showing” by using sensory details in your writing also applies to children’s picture books. For example, in Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day, author Judith Viorst doesn’t need to repeatedly remind readers how annoying Alexander becomes throughout the day. She does this by focusing on the frustrating events that she finds Alexander, and using the illustrations to explain how she feels Alex. Consider her disgusted expression and her concisely crossed arms in the image above.

One tip to make sure your picture book shows rather than tells is to look for instances of the words “is”, “are”, “was” or “were”. double check to see if any of the sentences associated with these words tell the reader something you could show them instead.

Review this golden rule of writing with this comprehensive “show, don’t tell” guide.

6. edit and search comments

As we just mentioned, every word really needs to count in a book with so few words. So the first step of your editing process should be to go through your book line by line, and for each one consider: is this line crucial for my story? If the answer is yes, carry on. If it’s no, remove it!

After you’re done, proofread your manuscript for any spelling or grammatical errors.

once you’ve polished your manuscript as much as possible, it’s time to seek feedback from the most honest beta readers: the kids!

If you have friends or relatives with children, ask them to read your book to their little ones, taking note of their comments. Bonus points if you can see someone reading your book to a child, as you’ll not only get their reaction, but also get a chance to hear what your book sounds like read aloud by someone else.

There are also several great communities for children’s book authors that you can join to get reviews and feedback.

Finally, if you want to be really sure that your picture book is ready to capture the imagination of young readers, consider working with a professional publisher. Publishers rely on their knowledge of the publishing market they specialize in to inform their feedback, so the benefits an experienced children’s book editor can bring to your story are significant.

See Also: Top 10 Books for ADHD Parents to Understand a Child with ADHD

If you want to dive into the idea of working with a professional editor, you can sign up for a free reedsy marketplace account and request quotes from different children’s publishers at no cost, including some who have worked with popular authors like r.l. meadows of stine and daisies!

At this point, your children’s picture book should be complete! now you can turn your attention to illustration and publishing.

7. illustrate your illustrated book

If you’re hoping to have your book traditionally published, you can skip this step and go straight to the next. In just about every case, if your book is acquired by a publisher, they will want to choose their own artist to take care of the illustrations. In fact, sending a publisher your already-illustrated manuscript could harm your chances of landing a book deal as it may prevent editors from seeing how your book fits them. Think of it as going to see a house you’re interested in buying. If the place is covered with the current owner’s personality, you might have a tougher time seeing yourself living there. If the house is presented as more of a clean slate, you might walk in and spot the potential right off the bat.

Now, if you plan on self-publishing your children’s picture book, you’ll definitely want to hire a professional artist to do the illustrations, unless you’re Eric Carle and have excellent writing and illustrating skills. here’s how to find the right illustrator for you.

1. get an idea of the kind of illustrations you like.

Ultimately, the illustrator you hire will have insight into what types of illustrations tend to work with the type of book you’ve written. That said, you absolutely should go into the process of finding the right collaborator with an idea of what you like. head to your local bookstore and spend time browsing the picture books there. take notes on the elements of the illustration that you like or dislike. Alternatively, scroll through these examples of book illustrations for inspiration.

2. set a budget, summary and deadline.

These are three key things to keep in mind before you start looking for an illustrator. you want to know how much you can afford to spend on illustrations, how much work you need to do (for example, how many pages do you need to illustrate and what type of illustrations are you looking for), and what date do you need the work completed by. All of this information will play an important role in finding the right designers for your project. but remember, you may need to adjust your expectations as you start talking to illustrators and start to get a sense of how much they typically charge and how long the average turnaround time is.

3. Look closely at the illustrators’ portfolios.

This is the best way to create a list of illustrators you are interested in working with. In addition to getting an idea of their work and if it’s your thing, you should keep an eye out for their credentials: have they illustrated picture books for your age group before? Have they illustrated characters that look like yours before? and so on.

4. contact illustrators.

Once you’ve finalized your list of finalists, contact the illustrators and talk to them about your book and the details of the budget, brief, and deadline you’ve worked out beforehand. If you’re looking for a safe environment to search for experienced illustrators, sign up for a free Reedsy account to gain access to our vetted marketplace of professional illustrators. you’ll be able to check their portfolios and past work experience with the click of a button!

8. publish your picture book

If you’re still not sure which publishing route you want to take, here are a few things to keep in mind.

self-publish an illustrated book

If you want to dictate the amount of time it takes to get your book to market, have the final say on all creative decisions, and keep a much higher percentage of royalties, then self-publishing your picture book is probably the best option. move for you.

That said, self-publishing also means you have to be willing to do all the marketing and distribution work yourself, and the costs associated with publishing your book will have to be borne out of your own pocket.

For many authors, one of the biggest draws of self-publishing is accessibility. The picture book market is notoriously competitive when it comes to getting a publishing deal. it can be a very long game with an unclear outcome. so if your primary goal is to get your book published and available to young readers, stick to desktop publishing.

here are some resources to help you along the way:

- how to self-publish a children’s book [blog post]

- guide to marketing a children’s book [free course]

- guide to print on demand [blog post ]

traditionally publish an illustrated book

In a plot twist everyone was expecting, the benefits of traditional publishing coincide with the potential dangers of desktop publishing. Those benefits include wider distribution and increased chances of seeing your book in physical stores, a production team that will work on the book at no cost to the author, an advance against sales, and at least a degree of book promotion. — though even with traditional publishing, authors are also expected to shoulder a portion of the marketing efforts.

On the flip side, there’s the inaccessibility, slower release timeline, lower creative contribution, and lower royalty percentage that we also mentioned earlier.

If you like traditional publishing, don’t forget to consider independent publishers and small publishers, who are more likely to take a chance on an unknown children’s author.

Here’s some further reading to answer more of your trade publishing questions:

- how to publish a children’s book [blog post]

- how to write a query letter [blog post]

- how to identify the target market for your children’s book [blog post]

Finally, whether you’re planning to self-publish your book or go the traditional route, this free online course is a great resource that breaks the process of publishing a picture book into manageable steps.

And there you have it: how to write a children’s picture book in eight steps. Whether you came to this blog post at the beginning of your writing journey or in the middle of the publishing process, remember to keep the goal of reaching young readers in mind every step of the way. bonus points if you can approach this often challenging endeavor with a childlike sense of curiosity and fun 😊

Are you in the process of writing an illustrated book? Tell us about it, and ask any questions you may still have, in the comments below!

See Also: What to Read While Youre Waiting for The Winds of Winter | Frostbeard – Frostbeard Studio